Latin America, like most of the world outside of Europe and the U.S., has traditionally been on the periphery of science. Colonialism and neo-colonialism, lack of funding and infrastructure, and the unwillingness of the international scientific community to pay attention to the science produced in the South have all relegated Latin America and the Caribbean to a secondary role. But what of those scientists within this region who were themselves made peripheral, not only to scientific centers but within their own societies? Female scientists in Latin America and the Caribbean have struggled against these mutually-reinforcing challenges since (at least) the early colonial period, and although they have long done excellent work in various scientific fields, the male-dominated scientific establishment (much less international science on the whole) has only recently begun to recognize their merit and numerous achievements.

Female scientific knowledge, especially relating to nature and health, were and are highly valued in many indigenous societies. Women needed to understand the properties, uses, and benefits of various natural resources (animal, plant, mineral) in order to provide for and take care of their families while also creating specialized niches in which they were recognized for their expertise (Bain 1993). In providing local healthcare, men often acted as curanderos or shamans while women reigned in obstetrics and midwifery. According to Paula M. Sesia, indigenous women's prenatal care developed through generations of empirical experimentation, a circumstance that continues to engender a significant amount of respect from the local community despite the introduction of bio-medicine (Sesia 1996).

With the Spanish conquest, indigenous and European ideas about gender collided, and while there was much mutual acculturation, the political dominance of the Spaniards went a long way to institutionalizing Spanish gender norms. From the colonial era until well into the nineteenth century, there was almost no space in Latin America or the Caribbean for female scientific knowledge. Even the most learned women, like Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz (seen in the sources), faced tremendous social and religious pressures to renounce the pursuit of knowledge.

The independence era, however, opened some new opportunities for practicing science. Most of the new American nation states strove for modernity, and some countries (especially Mexico and, later, those of the Southern Cone) realized the potential of women to have a positive impact on society through the practice of medicine. Historian Lee M. Penyak noted how mid-nineteenth century Mexico encouraged women to train in obstetrics and midwifery (traditionally female sciences on both sides of the Atlantic) and the obvious talent of many of these women demonstrated to male doctors that women were indeed capable and they were soon allowed into other medical spheres (Penyak 2003).

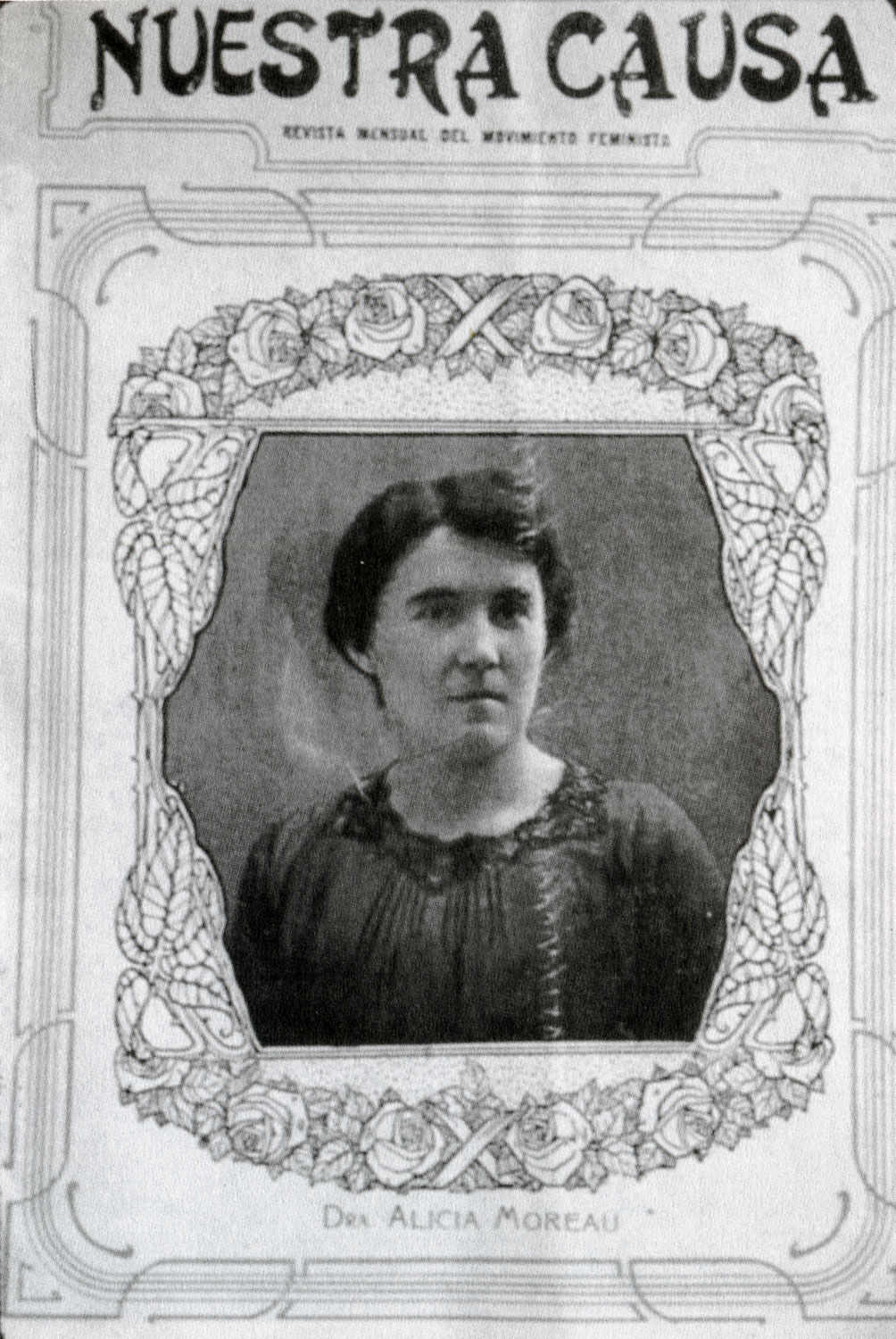

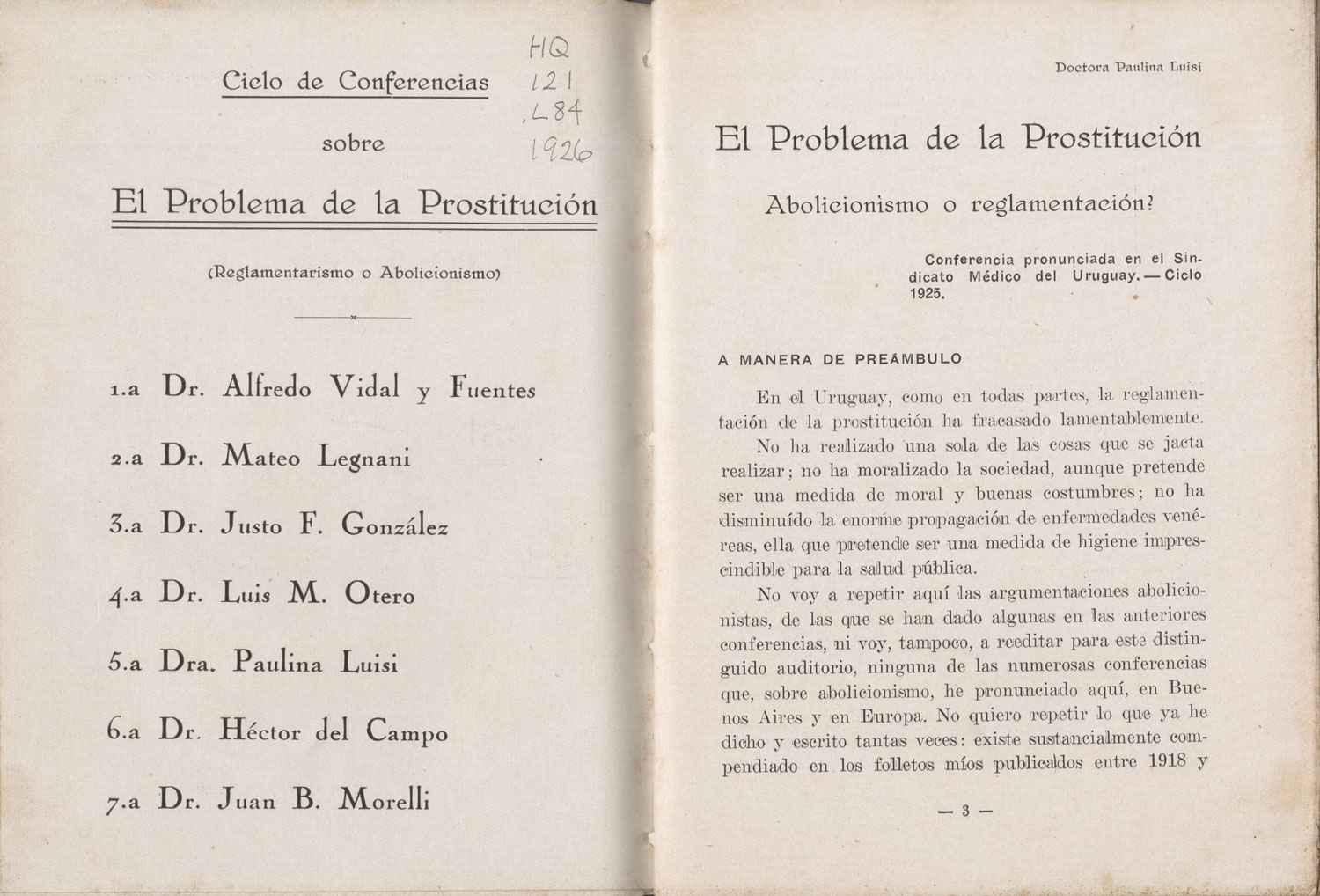

In the Southern Cone countries (Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay), the first generation of female doctors, those who earned medical degrees circa 1910, were often leading figures in national (and international) feminist movements. Doctoras like Alicia Moreau and Paulina Luisi tried to liberate women both politically and biologically by campaigning for universal suffrage and promoting sexual education. Their version of sexual education and their fight against prostitution and alcoholism were closely tied to the tenets of social hygiene and eugenics, both of which were very popular in early twentieth century Latin America. Educating women about their bodies was thus necessary to both achieving social equality and improving the genetic makeup of the nation on the whole (Lavrin 1995). Despite many obstacles, these doctoras were instrumental to passing legislation on women's and children's rights and, through vehicles like the Pan American Scientific Congresses, even helped spread these progressive ideas to North America (Miller 1986).

In the last thirty years, women scientists in Latin America have come much closer to equality with their male counterparts. Although some disciplines like physics, engineering, and certain highly specialized medical fields are still dominated by men, females are enrolling in technical schools, scientific post-graduate programs, and medical school at ever-rising rates. They face many of the same challenges as Latin American male scientists, such as lack of jobs in their field, and many aspects of Latin American society remain quite sexist. It is a significant figure, though, that about 47% of people working in the sciences in Latin America are women, a number almost 20% higher than the world average. While there are still gender (and race and class) barriers in Latin American science, the dramatic advancements made by female scientists (especially in the last 100 years) is a testament to the hard work, tenacity, and natural talent of an increasingly large body of women who refused to stay on the periphery.

Questions for further exploration:

- How have indigenous women skilled in the sciences coped with the pressures of westernization, capitalism, and "modernity"? Consider the source in this topic on indigenous midwives, but see also the topics on Healers and Indigenous Medicine and Inca Weaving.

- Compare the approach to women's health and social hygiene of the doctoras Paulina Luisi and Alicia Moreau to that of early twentieth century Latin American eugenicists and hygienistas in general. How did each approach perceived problems such as women's role in society, social degeneration, and the role of hygiene in public and private life?

- Concepcion Campa Huergo, seen in this topic's sources, is one of several Latin American female scientists in the recent past to earn international renown for her work. Research a twentieth century Latin American female scientist who is not noted in the sources. Discuss her contributions to science, any specific geographic or gender obstacles she has overcome, and what--if any--impact being a Latin American woman has had on the kind of science she does.

- Throughout the twentieth century there have been several important connections between female scientists in Latin America and those in the United States. These bonds were fused by individuals like Agnes Chase and Alicia Moreau who travelled across the Americas as well as by networks like the Pan American Conference on Women that brought progressive females from both regions together. Compare the twentieth century relationship between female scientists in the U.S. and Latin America with the overall scientific relationship of the two regions. Make an argument as to why these relationships are similar or different.

- Consider how the kinds of science that women have practiced in Latin America have changed from the pre-Columbian era to the present. What social, international, or personal choices have driven these changes?

Further reading:

Bain, Jennifer H. "Mexican Rural Women's Knoweldge of the Environment." Mexican Studies/ Estudios Mexicanos. 9: 2 (Summer 1993): 259-174.

Henson, Pamela M. "Invading Arcadia: Women Scientists in the Field in Latin America, 1900-1950." The Americas. 58: 4, Field Science in Latin America (April 2002): 577-600.

Lavrin, Asuncion. Women, Feminism, and Social Change: in Argentina, Chile, & Uruguay, 1890-1940. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

Miller, Francesca. "The International Relations of Women of the Americas, 1890-1928." The Americas. 43: 2 (October 1986): 171-182.

Munoz, Estela Altuna and Frederick S. Weaver. "'Out of Place': Ecuadorian Women in Science and Engineering Programs." Latin American Perspectives. 24: 4, Ecuador, Part 2: Women and Popular Classes in Struggle (July 1997): 81-89.

Penyak, Lee M. "Obstetrics and the Emergence of Women in Mexico's Medical Establishment." The Americas. 60:1 (July 2003): 59-85.

Powers, Karen Vieira. Women in the Crucible of Conquest: The Gendered Genesis of Spanish American Society, 1500-1600. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2005.

Sesia, Paola M. "'Women Come Here on Their Own When They Need to': Prenatal Care, Authoritative Knowledge, and Maternal Health in Oaxaca." Medical Anthropology Quarterly, New Series. 10: 2 (June 1996): 121-140.