In the eyes of the European conquerors and settlers of the sixteenth century, potential wealth seemed to be everywhere in colonial Latin America. Vast deposits of gold and silver, New World biota, and a climate and soil well suited for growing cash-crops all promised to make a fortune overnight for Iberian settlers. Yet who would mine the ore and harvest the sugar? There were not enough European laborers to extract the latent riches of the Americas (and many of them were unwilling to do manual labor), so slaves, both African and Native American, were pressed to toil for wealth that they would never share. Throughout Latin America, a pattern developed where a profitable commodity would be discovered that was fit for exploitation by slave labor. Shortly thereafter, slave labor would become seen as so necessary to the continued production of that product that the region would develop into a slave society, one in which the social structure, economy, and everyday life were totally dependent on slaves.

The first slaves to the European colonial system were Native Americans, yet opposition to this practice quickly developed among Spaniards like Bartolome de las Casas, who argued successfully that Indians did indeed have souls and were capable of being Christians. Such arguments led the Crown to forbid the enslavement of Indians in the mid sixteenth century (although it did persist in many areas of Latin America). Spaniards thus developed a new system for exploiting Indian labor, the encomienda, a system in which local Indians owed labor to an elite Spaniard (an encomiendero) as tribute and payment for their protection. Economic historian Timothy J. Yeager noted how the Spanish Crown preferred encomienda to outright slavery in the sixteenth-century because it provided a structure for imperial expansion and Christianizing the indigenous peoples. Yet this system of coerced labor was not suited for exploiting new sources of wealth; the Indians in this relationship were not obliged to travel in order to fulfill their tribute and, as new mines and cash-crops were constantly being discovered, elite Iberians needed a mobile labor force (Yeager 1995). Slaves could reproduce (thus creating new transferable property), be sent anywhere, sold, traded, inherited, and forced to work under horrible conditions with minimal rest, attributes perfect for a capitalist in search of reliable labor at minimal long-term cost.

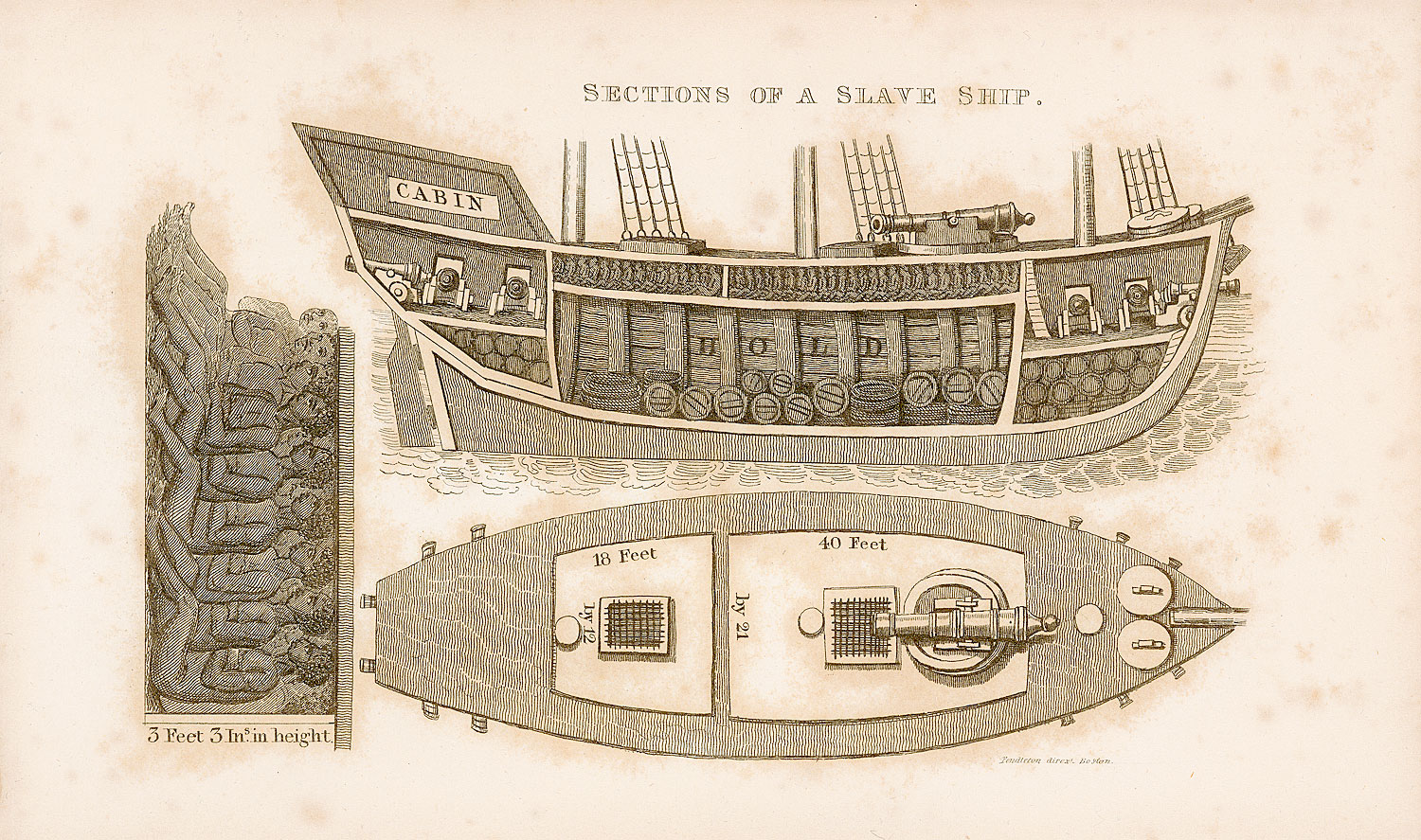

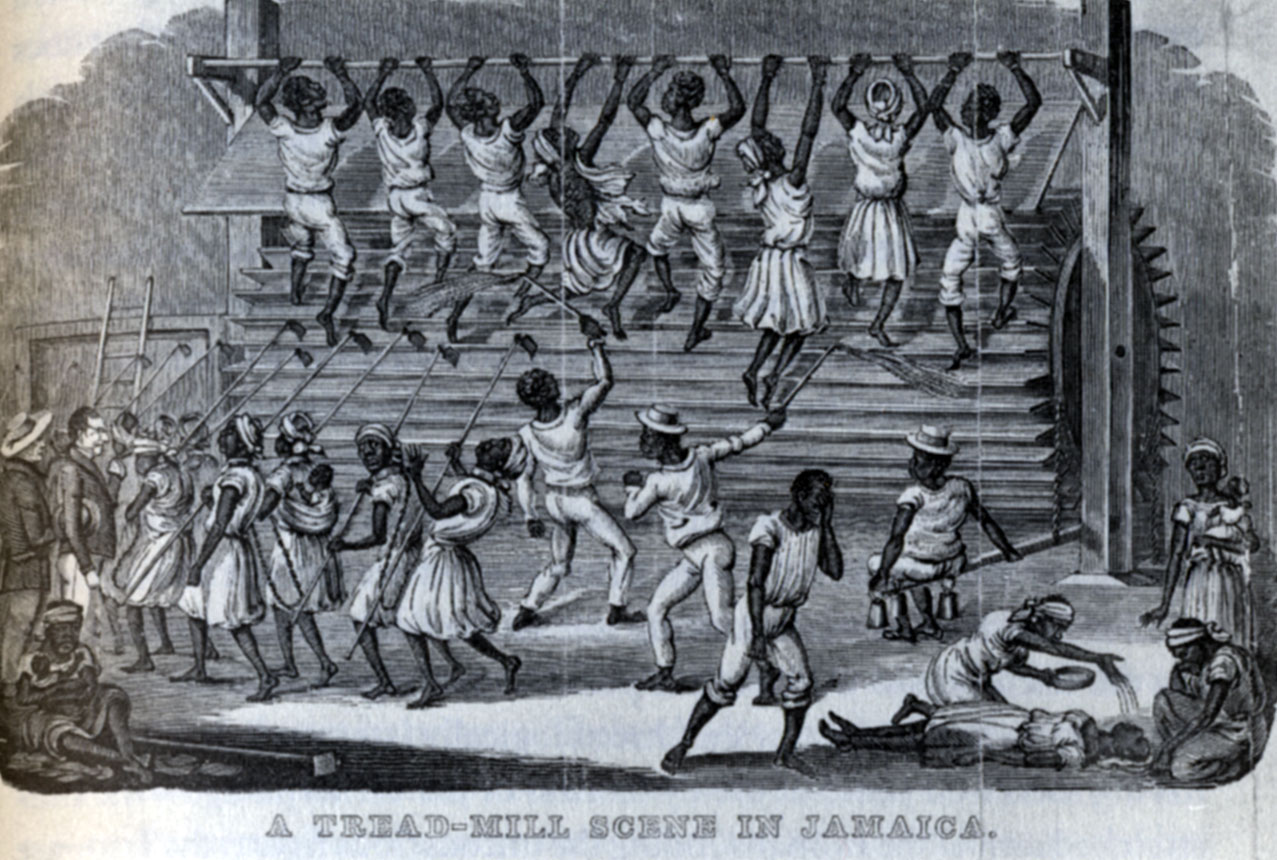

In the mid sixteenth century, settlers turned increasingly to imported Africans to do their work for them. All told, approximately 5 million of the 14 million Africans sold into slavery died during their transportation or soon after their arrival in the New World. Those who lived to work on American plantations (sugar, indigo, tobacco, cotton, coffee, cacao, rice, etc.) or in mines faced a new kind of hell; work days lasted about eighteen hours, living conditions were squalid, diets were poor, and their treatment was often wicked. The horrors of the so called "black legend," the idea that Spanish colonists were crueler than their Anglo-American counterparts, actually describe both British and Iberian slave societies. British sugar islands like Barbados and Jamaica were renowned for high death rates and savage forms of punishment (see the extract from Olaudah Equiano's autobiography in this topic's sources). Despite intense efforts to dehumanize Africans on board slave ships and in plantations, Africans brought culture, technology, and genetic gifts with them to the New World. African heritage and humanity survived its enslavement and the diverse racial and cultural blends of Latin America and the Caribbean are a testament to their endurance.

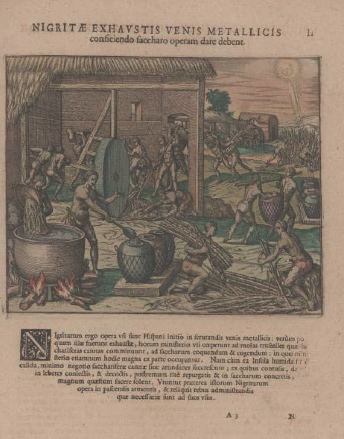

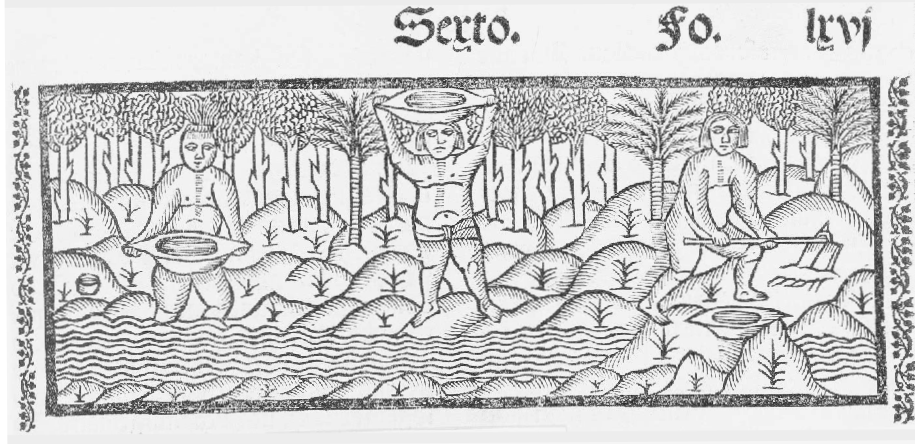

Of all African slaves brought to North and South America, about two-thirds were set to work on sugar plantations, like the one shown in De Bry's engraving from 1595. The sugar revolution (c. 1630-40) of the British Caribbean was the impetus for much technological, economic, and agricultural innovation. Technology even came to play a part in the punishment of slaves. According to Diana Paton, technocrats in Jamaica considered flogging to be an unproductive form of punishment and began forcing slaves to "dance" on vertical treadmills because it was both excruciating and productive (Paton 2004). Although sugar was not exclusively responsible for bringing slavery to New World plantations, where cacao, tobacco, cotton, and indigo also created slave societies, the prevalence of sugar plantations and their exceptionally harsh conditions make it the quintessential catalyst of African-American slavery.

Slavery is the dark side of the technological, mineralogical, and agricultural achievements that made the Americas a source of riches for European empires. The application of mercury to silver mining to increase production, improved agriculture for New World products like cacao, and empirically tested cultivation of existing cash crops like sugar served to create slave societies almost instantly. Slave ships themselves, like the two portrayed in the sources, were advanced pieces of technology, and the plantation system of importing slaves and exporting sugar, metals, or coffee would not have been possible without it.

Significantly, it was ideological changes, not technological improvements, which disintegrated slavery in the Americas. Using technology to be more productive, such as new sugar refinement techniques, the cotton gin, or improving crop strains, only fed the monster of American slavery. It is a stark reminder that technological advancement often precludes social progress.

Questions for further exploration:

- Which advancement of the early modern period--technological, scientific, agricultural, etc.--was most responsible for instigating American slavery? Was the relevant advancement or contemporary ideology more important?

- In what ways were slave ships technologies that advanced plantation slavery in the New World? Consider both the more concrete effects (demography, economy, etc.) as well as the less tangible results (psychological, cultural, social, etc.).

- Compare the two images of sugar plantations, De Bry's 1595 engraving and the 1749 "Art of Making Sugar." How had sugar plantations changed in the 150 years between these two images? How had the manner of depicting them changed (e.g., what elements did the artist chose to emphasize and why)?

- How did science-based attitudes towards slaves change with the abolition of Afro-Latin slaves? How did they stay the same? See other topics, inlcuding Eugenics, Criminology, and Darwin.

- Compare European attitudes towards Africans with their attitudes towards Indians. How did science influence or reflect the discrepancies in Europe's racial perceptions? Some possible sciences to consider are (you may focus on one or more): geography, anthropology, pharmacology, climatology, mineralogy, botany, ethnology, physiology, medicine, agriculture, criminology, navigation, and empirical science.

Further Reading:

Bryant, Sherwin K. "Finding Gold, Forming Slavery: The Creation of a Classic Slave Society, Popayan, 1600-1700." The Americas. 63: 1 (July 2006): 81-112.

Cuello, Jose. "The Persistence of Indian Slavery and Encomienda in the Northeast of Colonial Mexico, 1577-1723. Journal of Social History. 21: 4 (Summer 1988): 683-700.

Galloway, J.H. "Agricultural Reform and the Enlightenment in Late Colonial Brazil." Agricultural History. 53: 4 (October 1979): 763-779.

Higman, B.W. "The Sugar Revolution." The Economic History Review, New Series. 53: 2 (May 2000): 213-236.

Menard, Russell R. Sweet Negotiations: Sugar, Slavery, and Plantation Agriculture in Early Barbados. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006.

Paton, Diana. No Bond but the Law: Punishment, Race, and Gender in Jamaican State Formation, 1780-1870. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

Rediker, Marcus. The Slave Ship: A Human History. London: Viking Press, 2007.

Yeager, Timothy J. "Encomienda or Slavery? The Spanish Crown's Choice of Labor Organization in Sixteenth-Century Spanish America." The Journal of Economic History. 55: 4 (December 1995): 842-859.