In the dry mountains of Chile, state-of-the-art optical telescopes with 8-meter lenses are probing the distant reaches of space and capturing fantastic images of stars and galaxies that are changing how scientists think about our universe. 3,494 miles away, in a volcanic crater in Puerto Rico, an 18.5 acre radar dish is sending and receiving waves that U.S. astronomers read to learn about small particles in our solar system. 2,346 miles south of this huge dish, Bororo Indians in Matto Grosso, western Brazil, lie observing the ordered progress of cosmic movements and use this empirically gleaned knowledge to bring better order to their own society. 1,431 miles from there, in the Yucatan Peninsula, the silent remains of long-abandoned Maya observatories continue to bear witness to the precise astronomy practiced in ancient Mesoamerica. All of these very distant and different observatories and observers are focused on the same impossibly vast sky, and each has used the stars to make valuable insights that give structure to their vision of the cosmos.

For well over 1500 years, Latin America has held an important place in astronomy and cosmology, sciences that are quite literally universal, and many of the world's best observatories are and were in Latin America and the Caribbean. Both locals (scientists and curious laypeople alike) and foreign specialists practice stargazing in this region known for its atmospheric and topographic advantages. In the pre-Columbian era, Latin America's observatories and astronomical knowledge surpassed anything in contemporary Europe. The Maya, for one, used specialized observatories like the Caracol (seen in the sources) to create detailed charts of stellar and planetary movements that facilitated a highly detailed dating system.

Europeans, though, were learning to use the stars to cross the open ocean, an experience that drove European astronomy forward at an incredible pace. The needs of precise navigation required better and better instruments (like the astrolabe and backstaff in the sources) that were tested at sea and developed in Iberia's new scientific institutions, like the Casa de Contratacion. More importantly, Europe's improved navigation techniques brought the Old and New Worlds together, a fusion of cultures that, among many other things, forever changed Latin American astronomy.

While the well-trained naked eye can learn much from stargazing, astronomy is a science that progresses with and because of technological changes, and the fusion of ever-improving telescopes and the opportunities to view the southern skies that Latin America affords has consistently yielded impressive results. Modern western observatories were springing up throughout the Americas by the Enlightenment era, including one in Nueva Granada operated by Francisco Jose de Caldas and a temporary observatory in Baja California that, along with 150 others teams around the world, observed the transit of Venus in 1769.

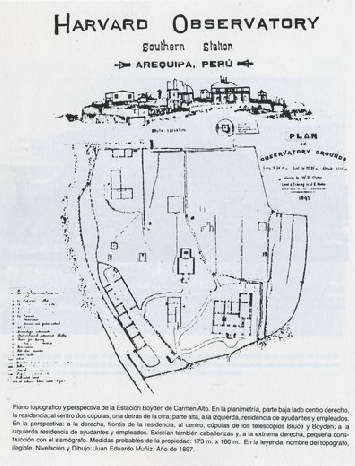

By the late nineteenth century, the U.S. replaced both Europeans and Latin Americans as the primary stargazers of Latin America, setting up observatories in Chile and Peru that greatly expanded collective knowledge of southern skies. U.S. astronomical dominance, though, was closely tied with its neo-imperial attitude towards its southern neighbors. In the years since World War II, this process accelerated even further as highly funded U.S. astronomers brought "big science" to Latin American astronomy, using technologies and resources that local observers could not hope to match. Indeed, according to historian of science W. Patrick McCray, modern telescopes (like the Very Large Telescope in Chile or the huge dish in Puerto Rico) have fundamentally changed what it means to do astronomy. The hours once spent alone at night with a telescope have changed to reading computer-gathered information off of a monitor (McCray 2004).

Chile is the country most often associated with modern astronomy in Latin America, and it is one of the sky-watching centers of the world. Since 1963, it has been home to large U.S. and European observatories, and now proudly hosts both Europe's Very Large Telescope and one of two U.S. Gemini telescopes. Despite its many successes, astronomy in Chile has been fraught with tension. While Chile has enjoyed a good working relationship with the U.S. (due largely to the 10% "glass time" that the U.S. gives Chile on its telescopes), Chileans have resented the imperialist attitudes of European astronomers. Political and terrestrial instability (characterized by Pinochet and earthquakes, respectively) have also problematized the multi-hundred-million dollar facilities in Chile's Atacama Desert. The natural clarity of Chile's vistas and the excellent telescopes have not, however, fostered the kind of national science that many have hoped for in Chile. While natural resources in other Latin American countries (like Argentine fossils) have led to regional scientific specialization, Chilean astronomers remain a rarity.

While vistas in many of the world's observatories are worsening due to air and light pollution, enclaves like the Chilean mountains are becoming increasingly valuable commodities. The natural advantages of such areas will continue to attract advanced technologies from the world's scientific elite and Chile may yet grow further in importance for the international community of astronomers. For Latin American astronomy, the sky is the limit.

Questions for further exploration:

- Compare the observatories shown in the sources. Although technological differences can be noted, try to focus on the differences in the approach to astronomy and goals of these observatories. What, if any, changes have occurred in the purpose of astronomy in Latin America?

- How has technology changed cosmology in Latin America? Think about this broadly.

- How is Chilean astronomy similar and different to scientific specialties of other Latin American countries? You can compare it with one other country or do a broader overview. (Some possibilities are Brazilian nuclear power, Mexican mining, Caribbean agriculture, Peruvian high altitude studies, Argentine paleontology, Brazilian tropical diseases, etc.).

- Consider one of the astronomic expeditions to Latin America. Some questions to consider include: Was this expedition imperialistic in some way? Or was it perhaps meant to benefit science universally? How did the foreign and local scientists interact?

- Would astronomy in general be the same without Latin America? Explain your response.

Further Reading:

Appenzeller, Tim. "Astronomers Struggle to Keep Up With Their Opportunities." Science, New Series. 267: 5199 (February 1995): 819-820.

Aveni, Anthony F. Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1980.

Engstrand, Iris Wilson. Royal Officer in Baja California, 1768-1770: Joaquin Velazquez de Leon. Los Angeles: Dawson's Bookshop, 1976.

Fabian, Stephen. Space-Time of the Bororo in Brazil. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992.

Hammond, Allen L. "Big Astronomy in Chile: The Southern Observatories Come of Age." Science, New Series. 198: 4323: (December 1977): 1235-1239.

"Largest Radio-Radar Telescope Unveiled." The Science News-Letter. 84: 21 (November 1963): 323.

McCray, W. Patrick. Giant Telescopes: Astronomical Ambition and the Promise of Technology. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Rasmussen, Wayne. D. "The United States Astronomical Expedition to Chile, 1849-1852." The Hispanic American Historical Review. 34: 1 (February 1954): 103-113.