Since its independence in 1822, elite Brazilians have considered their nation to be destined for greatness (grandeza) and to rank among the world's modern powers. Yet according to Lincoln Gordon, a scholar of Brazilian trade and energy policy, this nationalistic aspiration has been continually upset by the shortcomings of Brazil's uneven economy, which has relied largely on the exchange of its raw materials for goods manufactured abroad. Such a trade relationship allows little room for long-term growth. As part of the effort to launch itself into a first world economy while simultaneously proclaiming its greatness, Brazil has undertaken an extensive nuclear energy program that now includes two nuclear power plants as well as a high-tech centrifuge capable of refining the abundant domestic uranium supply.

In the post World War II era, nuclear technology has been the international hallmark of greatness, power, and modernity. Thus the Brazilian military government of the late 1960s created secret facilities for the production of atomic weapons (publicly denounced and discontinued in 1990) and, in 1970, approved the construction of a nuclear power plant at Angra dos Reis, a bay about two-hundred and fifty kilometers south of Rio. The plant, called Angra I, was finally completed in 1982 and a second reactor at the same site, Angra II, began producing electricity in 2000. Combined, these two plants produce 2000 megawatts per hour, about 4% of the total electricity generated in Brazil. Hydroelectric power, generated at dams on Brazil's many large rivers, is by far the largest source of energy and accounts for nearly 85% of the total output.

Yet the efforts to achieve grandeza through nuclear technology faced the same economic difficulties as earlier attempts at large scale industrialization. Following the advice of the United Nations' Economic Commission on Latin America (ECLA) in the mid-twentieth century, Brazil sought to bolster domestic manufacturing in order to lessen the dependence on foreign imports, a strategy known as Import-Substitution Industrialization (ISI). The nuclear plant, however, required not only foreign contractors for its construction but, once the Angra I power plant began operation in 1982, the importation of refined uranium to fuel the reactor. Thus the trade imbalance continued.

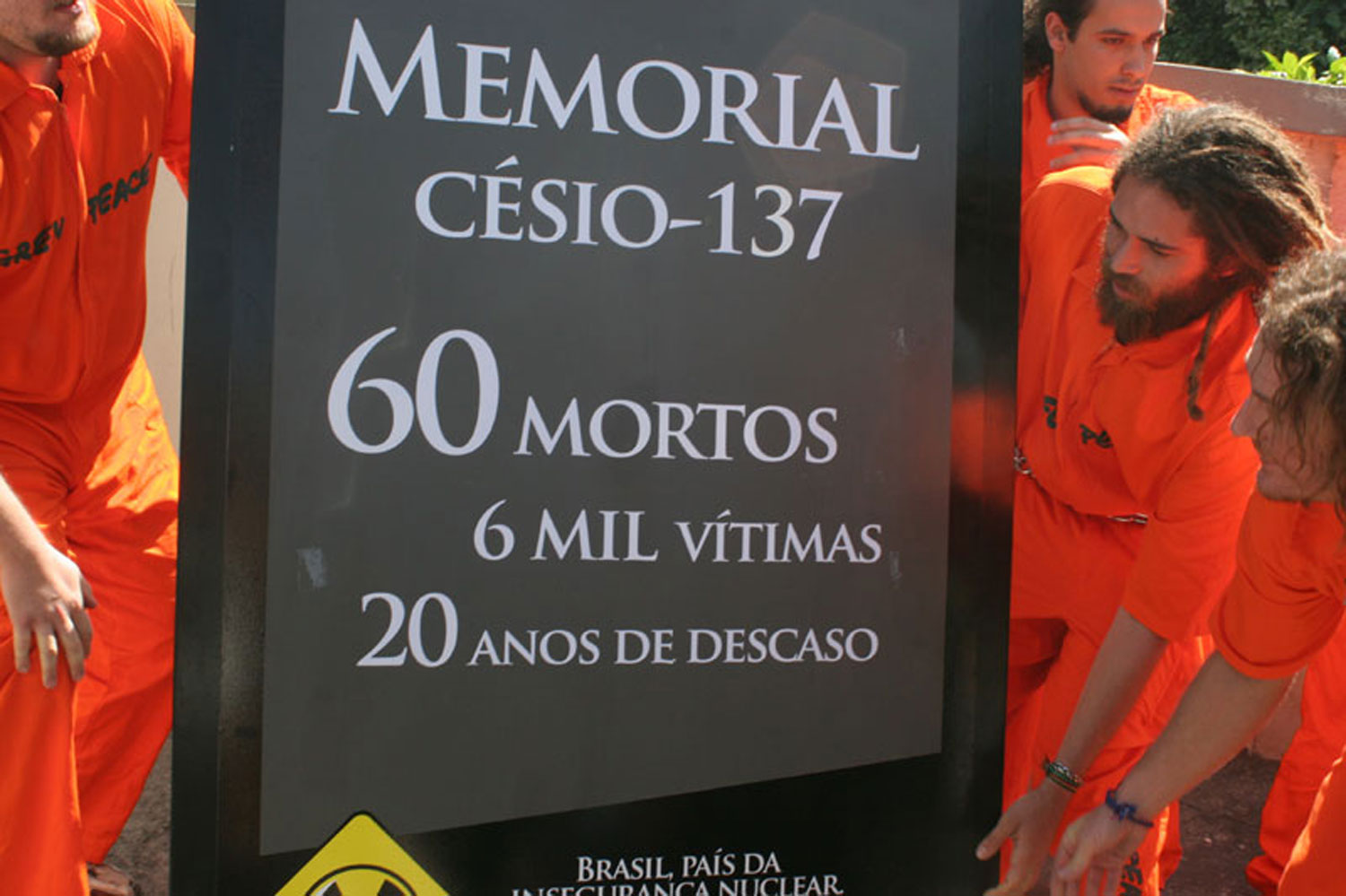

Nationalistic pride in nuclear power also wavered. Angra I and II produce little of Brazil's power and protests against nuclear energy by groups within Brazil have done much to decrease the prestige that policy makers had once hoped would come with nuclear capacity (see the source "Protest on Angra III"). Although Brazil signed the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty in 1998, its secretive policies have been cause for concern among some international organizations. Fears of a South American arms race between Argentina and Brazil have abated, but the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) still worries that Brazil might be attempting to produce nuclear weapons, especially at the new uranium centrifuge in Resende. Brazil has aggravated the situation by refusing international inspectors full access to the facility, resenting that it should be subject to restrictions and checks that were not imposed on the U.S. and other countries while they developed nuclear programs.

Furthermore, Brazil still faces an energy crisis; if its current rates of production do not increase significantly by 2010, it will encounter serious energy shortages. With the opening of the Resende uranium refinement plant in 2006, Brazil may opt to reinvest in nuclear power and build a third nuclear reactor at Angra. Although the Angra plant would be very expensive (about 3.5 billion USD) and produce less energy than new hydroelectric dams, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva is expected to approve the plant's construction.

Questions for further exploration:

1. With the opening of the Resende plant in 2006, Brazil became one of only six nations with the capacity to refine its own U-235. Furthermore, Brazil claims that the centrifuge at Resende is twenty-five times more efficient than those of the U.S. and France. In the context of Import-Substitution Industrialization and grandeza, how will the uranium refinement plant at Resende impact Brazil's attitude about nuclear power? About national pride?

2. How has nationalism been central to Brazil's nuclear program and what role does it continue to play today? Is the focus still on grandeza or have practical economic considerations become more important to policy makers (or, is it a combination of both)?

3. As seen in the sources for this unit, Greenpeace and other environmental groups have been protesting Brazil's nuclear plants. What are the environmental impacts of Brazil's nuclear program?

4. Hydroelectric power is often considered to be environmentally friendly. Why, then, is there such concern about the impact of building new dams on the Amazon that the government is considering approving another nuclear plant, despite the fact that it would cost much more and produce less power than a new dam?

Further Reading:

Gordon, Lincoln. Brazil's Second Chance: En Route to the First World. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2001.